How does one rid oneself of something buried far within: memory and the skin of memory. It clings to me yet.

Charlotte Delbo

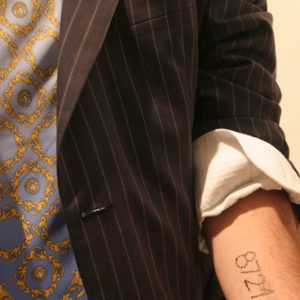

Häftling: I have learnt that I am a Häftling. My number is 174517: we have been baptized, we will carry the tattoo on our left arm until we die. … Only much later, and slowly, a few of us learnt something of the funereal science of the numbers of Auschwitz, which epitomized the stages of destruction of European Judaism.

Primo Levi

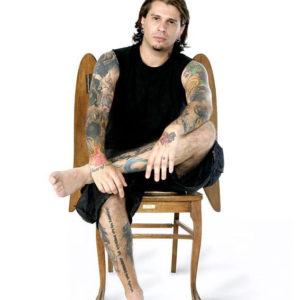

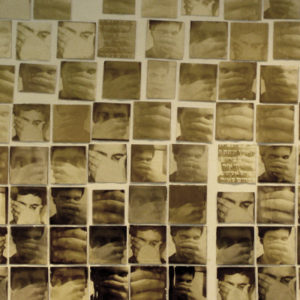

The number tattoo is the predominant, perhaps even the singular signifier of the Shoah. This one small part of the story of persecution, humiliation and dehumanization — no more than a stage in the Nazi process of genocide — has assumed the status of the very emblem of the event. This perhaps because it makes permanently visible how prisoners were stripped of their names, their identities, their past lives — how human beings were turned into bureaucratic ciphers, Häftlinge. Survivors who have chosen to keep the number “until [they]die” do so to bear witness to their own victimization and on behalf of those who have not survived to testify. Those who live with the Auschwitz tattoo live inside bodies that are memorials and media of defiance. Their arms are signposts alerting against the dangers of historical forgetting. But how is the number tattoo seen and received? How does it intervene in our present? How does it signify at a time when ornamental tattoos have become ever more popular forms of bodily display, carrying very different kinds of personal and cultural messages?

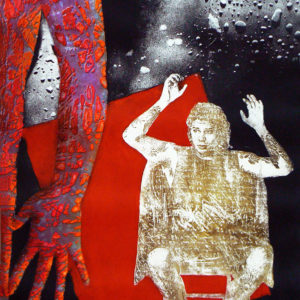

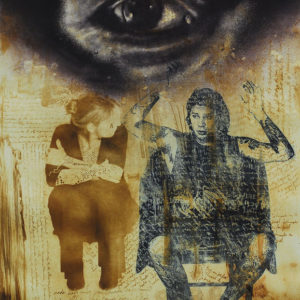

These are the questions that MirtaKupferminc — a daughter of Auschwitz survivors who grew up, as she says, “embraced by my parents’ tattoed arms” — raises in this memorial installation. Her parents could not hide their traumatic past from their children: it was literally inscribed onto their skin. And so their daughter also came to live inside the skin of memory.

But, with her artwork, she breaks out of this inherited trauma to provoke us, as visitors, into an act of co-witness. We are invited to look at the two kinds of tattoos, and to reflect on the differences between decorative choice and coerced numbering. We are asked to stop within the flow of everyday life and to sit, for a brief moment, on winged chairs that create a symbolic space of remembrance and contemplation. Voices surround us in a constant murmur, and if we just stop to listen, individual accounts of tattooing and being tattoed reach our ears.

And then, something else is being asked of us as well, something more troubling. Shall we extend our arm, offer it up to be marked? Will we get a decorative design or a number? Who will determine which and by what logic? And how, in the context of the memory of Auschwitz, can we live inside a body that has been marked in this way, even for a transient moment?

Here the daughter artist is performing a daring provocation. Staging the scene of the tattoo, she asks each of us to ponder what it might have been like, had we been there. Is this empathy? Identification? Appropriation of the trauma of the survivor? Those who respond to the call will have to decide for themselves.

Marianne Hirsch & Leo Spitzer